You won’t find Mary Magdalene in the legendary painting The Last Supper, but aside from the twelve apostles, Leonardo also depicted figures from both the Old and New Testaments in the background. A Slovak painter has even managed to identify the church Leonardo da Vinci painted more than 500 years ago.

Childhood Dreams Should Be Fulfilled

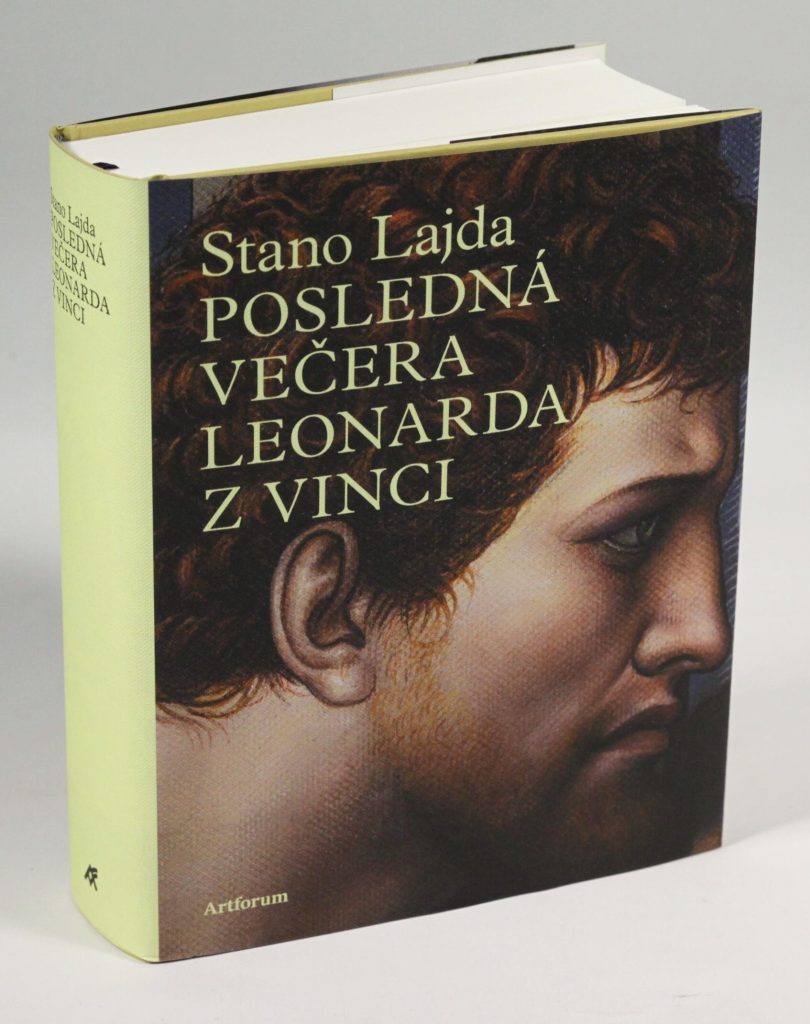

Stano Lajda is a painter, educator, and restorer who authored the first Slovak-language monograph on The Last Supper and Leonardo in general.

Following the twice-sold-out bestseller Leonardo’s Last Supper of Vinci, he compiled his latest scholarly findings into the book [REVEALED] The Secret of Leonardo’s Last Supper last year.

A native of Žilina, Lajda knows (almost) everything about Leonardo. As a child, he was mesmerized by a black-and-white image of this most famous Renaissance painting. Though it may sound cliché, it sparked a lifelong love.

Cenacolo, as it’s known in Italian, located in the refectory of the Dominican monastery in Milan, is now almost destroyed. That’s why Lajda was determined to fulfill one childhood dream: to see what the painting might have looked like the moment Leonardo set down his brush and declared it finished.

How to Understand Leonardo

Unlike conspiracy theorists, Lajda chose a difficult and thorny path to fulfill his dream. Instead of speculative theories or emotional guesswork, he committed to honest study and detailed research. Perhaps uniquely among artists, he was able to devote his entire life to reconstructing The Last Supper.

“As an artist, I had a close connection to understanding Leonardo’s working methods, which many found unconventional. I also drew from personal experience. And as a trained painting restorer, I understood the technique, degradation, and restoration of Leonardo’s mural very well,” says the winner of the Egon Erwin Kisch International Grand Prize for non-fiction literature.

Information Extracted from the Smallest Flakes

Lajda dedicated 10 years to reconstructing The Last Supper, and wrote a book that was sold out twice. His work also caught the attention of young documentary filmmakers.

He focused fully on the reconstruction between 2008 and 2019. His completed work was first exhibited at the Orava Gallery during the 500th anniversary of Leonardo’s death and later traveled across Slovakia, eventually reaching Rome.

“I’m a perfectionist—I cared about every detail. I tried to extract information even from the tiniest flakes that remained of Leonardo’s painting. You think about your work nearly all day, and often even dream about it at night. Ten years! Thousands of thoughts, pouring one after the other.”

Stano Lajda fully reconstructed The Last Supper, depicting 13 figures and focusing on details like the table, chairs, tablecloth, drapery, and the Sforza family crests (lunettes) placed in the refectory.

For practical reasons, in 2019 he completed an oil painting that is 2.5 times smaller than the original. Even so, it reaches impressive dimensions—3.5 meters long and nearly two meters high.

The Entire Bible in One Painting

To Lajda, it seemed too little that a genius like Leonardo would paint “just” The Last Supper at the height of his career. Could he have embedded a deeper meaning?

Late one night, while working, he noticed that the painting resembled an open book—what else could it be but the Bible?

He later developed the idea further and, by comparing depictions of Jesus and the apostles, concluded that the 12 figures Leonardo painted also symbolically represent other names from the Old and New Testaments.

The first on the left, Bartholomew the plowman, points to Adam, the first man formed from the earth. Andrew, with his ten spread fingers, recalls Moses, who brought down the Ten Commandments. Judas is modeled after Herod. And the parallels continue.

“When you can find that much evidence for each figure, it’s hard to call it coincidence. Two or three proofs—fine, maybe coincidence. But hundreds? That completely rules out randomness,” says Lajda.

The central figure of Leonardo’s entire painting is Christ. All lines and vanishing points converge on him. He becomes the center of the universe.

“Every one of Leonardo’s works contains profound spiritual symbolism and some message—often subliminal. That’s why his paintings are so timeless and elusive.”

The central figure of the scene is Jesus, who becomes the center of everything—not only the painting, but as Leonardo intended, the center of the entire universe. He is surrounded by his closest disciples, one of whom will soon betray him. On the eve of his suffering, he appears alone and forsaken. He knows what the coming hours will bring.

The Mysterious Landscape Behind Jesus

You won’t notice it in the ruined original, but if you look closely at Lajda’s reconstruction, you’ll see a heavenly, almost idyllic landscape through the window behind Jesus. A house, a garden, and a church can be spotted. The symbolism is clear: you feel a sense of family, safety, peace, and divine presence.

Now look at the tower. Is it ordinary and unimportant—or is it real and intentionally placed?

That octagonal tower kept Lajda up at night. Years of humble searching bore fruit again: it turned out to be the medieval Church of the Holy Savior in the Italian town of Capo di Ponte, where Leonardo likely took refuge from a plague that struck Milan in the late 15th century.

“I looked at maps of the area and nearly fell off my chair. Some hills near the tower matched Leonardo’s perfectly. From one of the several maps Leonardo himself drew, we know that he visited the Alpine valley of Val Camonica, including the specific place known as Capo di Ponte,” Lajda reveals.

The Romanesque chapel has remained unchanged for 800 years and inspired Leonardo with both its interior and exterior. “Why exactly that one? That borders on speculation. But I do offer one rather logical explanation. You can read about it in my book and form your own opinion,” he suggests.

The Duty to Explore

We, too, can dive into the mysteries of the genius Leonardo da Vinci: visit Milan, read Lajda’s books, attend his lectures or gallery exhibitions—or watch the documentary. Last year, public television aired the film The Last Supper: The Way, the Truth, and the Life.

The secrets uncovered by academic painter Stano Lajda through rigorous scholarly research are breathtaking. But are they necessary? Shouldn’t some mysteries remain hidden forever?

“There will always be plenty of mysteries. We’ll probably never know everything,” says Lajda.

“But if we didn’t explore, didn’t find out how to make fire, how to bake bread, how to forge a plowshare—we’d probably still be hopping through the trees or stuck in one place. That little word sapiens added to homo gives us the right—no, the duty—to explore, uncover, educate, and move forward.”

Original source: matusdemko.sk. Published with permission and free to re-distribute.